The field of behavioral ethics has seen considerable growth over the last few decades. One of the most significant concerns facing this interdisciplinary field of research is the moral judgment-action gap. The moral judgment-action gap is the inconsistency people display when they know what is right but do what they know is wrong. Much of the research in the field of behavioral ethics is based on (or in response to) early work in moral psychology and American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg’s foundational cognitive model of moral development. However, Kohlberg’s model of moral development lacks a compelling explanation for the judgment-action gap. Yet, it continues to influence theory, research, teaching, and practice in business ethics today. As such, this paper presents a critical review and analysis of the pertinent literature. This paper also reviews modern theories of ethical decision making in business ethics. Gaps in our current understanding and directions for future research in behavioral business ethics are presented. By providing this important theoretical background information, targeted critical analysis, and directions for future research, this paper assists management scholars as they begin to seek a more unified approach, develop newer models of ethical decision making, and conduct business ethics research that examines the moral judgment-action gap.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Scandals in business never seem to end. Even when one scandal seems to finally end, another company outdoes the prior disgraced company and dominates the public dialog on corporate ethics (c.f., Chelliah and Swamy 2018; Merle 2018). So, what is happening here? One common issue shows up repeatedly in cases of unethical behavior, which is that of knowing what is right yet doing what is wrong. This failure is classically understood as the moral judgment-moral action gap. Footnote 1

A main goal of behavioral business ethics is to understand the primary drivers of good and bad ethical decision making (Treviño et al. 2014). The hope is that with a better understanding of these drivers, organizations can implement structures that lead to more frequent and consistent ethical behavior by employees. However, business scholars are still working to discover what actually spurs ethical behaviors that improve profit maximization and corporate social performance.

This focus on understanding ethical decision making in business in a way that bridges the moral judgment-moral action gap has experienced an explosion of interest in recent decades (Bazerman and Sezer 2016; Paik et al. 2017; Treviño et al. 2014). These types of studies constitute a branch of behavioral ethics research that incorporates moral philosophy, moral psychology, and business ethics. These same interdisciplinary scholars seek to address questions about the fundamental nature of morality—and whether the moral has any objective justification—as well as the nature of moral capacity or moral agency and how it develops (Stace 1937). These aims are similar to those of prior moral development researchers.

However, behavioral business ethicists sometimes approach these aims without the theoretical or philosophical background that can be helpful in grappling with problems like the judgment-action gap (Painter-Morland and Werhane 2008). Therefore, this article provides a useful reference for behavioral business ethics scholars on cognitive moral development and its indirect but important influence on research today.

The first goal of this paper is to examine the moral development theory in behavioral business ethics that comes first to mind for most laypersons and practitioners—the cognitive approach. At the forefront of the cognitive approach is Kohlberg (1969, 1971a, b, 1981, 1984) with his studies and reflection of the development of moral reasoning. We also examine subsequent supports and critiques of the approach, as well as reactions to its significant influence on business ethics teaching, research, and practice. We also examine the affective approach by reviewing the work of Haidt (2001, 2007, 2009), Bargh (1989, 1990, 1996, 1997), and others.

We then consider research that moves away from this intense historical debate between cognitive and affective decision making and may be better for understanding moral development and helping to bridge the moral judgment-moral action gap. For example, some behavioral ethics researchers bracket thinking and feeling and have explored a deeper approach by examining the brain’s use of subconscious mental shortcuts (Gigerenzer 2008; Sunstein 2005). In addition, virtue ethics and moral identity scholars focus on how individuals in organizations develop certain qualities that become central to their identity and motivate their moral behavior, not by focusing on cognition or affect but by focusing on the practice of behavioral habits (Blasi 1993, 1995, 2009; Grant et al. 2018; Martin 2011). Each of these groups of behavioral ethics researchers have moved the discussion of moral development forward using theorizing that rests on different—and often competing—assumptions.

In this article, we seek to make these various theories of moral development explicit and to bring different theories face to face in ways that are rarely discussed. We show how some of the unrelated theories seem compatible and how some of the contrasting theories seem irreconcilable. The comparisons and conflicts will then be used to make recommendations for future research that we hope will lead to greater unity in theorizing within the larger field of business ethics.

In other words, the second goal of this paper is to provide a critical theoretical review of the most pertinent theories of Western moral development from moral psychology and to highlight similarities and differences among scholars with respect to their views on moral decision making. We hope this review and critique will be helpful in identifying what is best included in any future unified theory for moral decision making in behavioral ethics that will actually lead to the moral judgment-moral action gap being bridged in practice as well.

The third goal of our paper is to question common assumptions about the nature of morality by making them explicit and analyzing them (Martin and Parmar 2012). Whetten (1989) notes the importance of altering our thinking “in ways that challenge the underlying rationales supporting accepted theories” (p. 493). Regarding the field of business ethics specifically, O’Fallon and Butterfield (2005) found that a major weakness in the business ethics literature is a lack of theoretical grounding—and we believe this concern still requires attention. In addition, Craft (2013) notes that “perhaps theory building is weak because researchers are reluctant to move beyond the established theories into more innovative territory” (p. 254). As recommended by Whetten (1989), challenging our assumptions in the field of behavioral ethics will help us conduct stronger, more compelling research that will have a greater impact on the practice of business ethics.

For example, many business and management scholars are heavily influenced by long-held assumptions reflected in the work of Lawrence Kohlberg (1969, 1971a, b), one of the most prominent theorists of ethical decision making (Hannah et al. 2011; Treviño 1986; Treviño et al. 2006; Weber 2017; Zhong 2011). Like Sobral and Islam (2013), we call upon researchers to move beyond these assumptions. We will review a selection of research that explores alternate ideas and leaves past assumptions behind, leading to unique outcomes, which are of value to the field of management. Thus, in addition to making long-held assumptions clear, we will present critical analysis and alternative ways of thinking to further enhance the scientific literature on the topic.

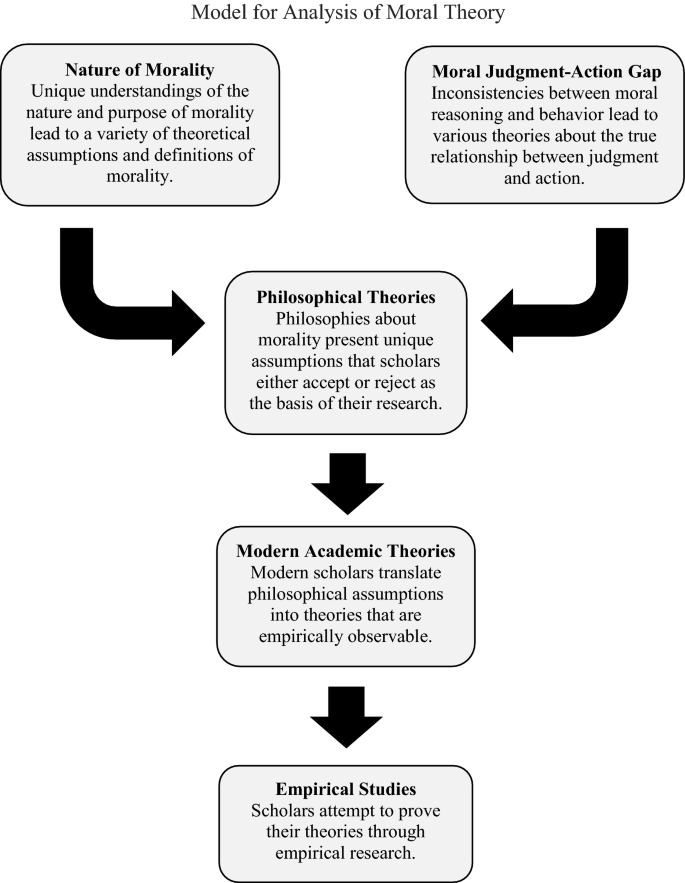

To accomplish this third goal, we will discuss links between definition, theory, and empirical study. This method of analysis is demonstrated by Fig. 1.

Our fourth and final goal is to note gaps in our current understanding of ethical decision making and to present directions for future research. We discuss these opportunities throughout the paper and more specifically in our summary.

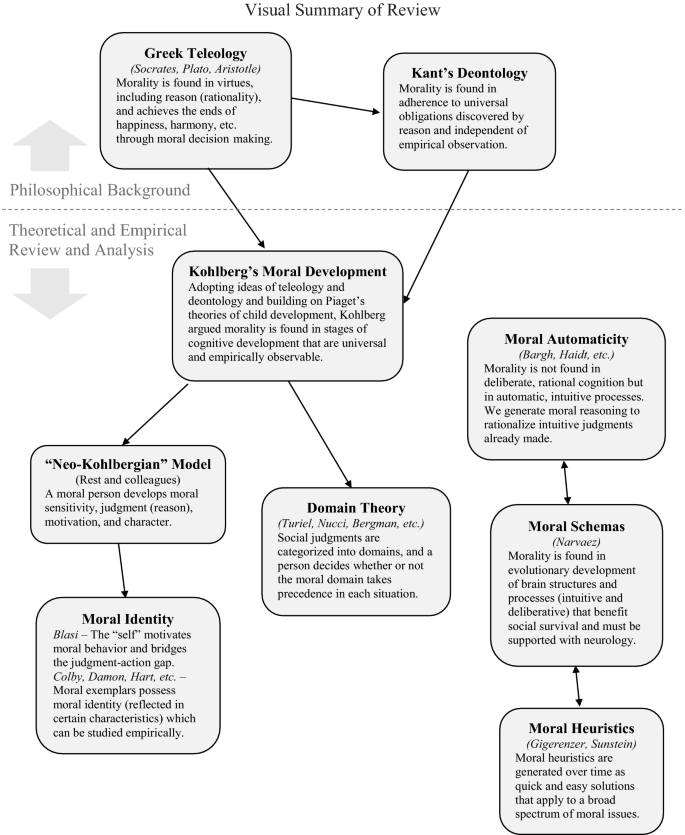

To accomplish these four goals, we begin with a review of the moral judgment-action gap and Greek and Kantian philosophy. After laying this theoretical background as a foundation for our discussion, we move deeper into a critical analysis. To begin this critical analysis, we discuss Piaget and Kohlberg, and the implications of their approaches. We then consider the Neo-Kohlbergian, Moral Identity, and Moral Domain research. The final section analyzes Moral Automaticity, Moral Schemas, and Moral Heuristics Research, as outlined in Fig. 2.

As mentioned above, behavioral ethics research indicates that the mere ability to reason accurately about moral issues predicts surprisingly little about how a person will actually behave ethically (Blasi 1980; Floyd et al. 2013; Frimer and Walker 2008; Jewe 2008; Walker and Hennig 1997). This ongoing failure is not for a lack of many thoughtful attempts on the part of researchers (Wang and Calvano 2015; Williams and Gantt 2012). The predictive failure has led to expressions of disappointment and frustration from scholars (Bergman 2002; Blasi 1980; Thoma 1994; Walker 2004).

The gap has led to a call for a more integrated and interdisciplinary approach to the problem in business ethics (De Los Reyes Jr et al. 2017). In agreement with that call for greater integration, we suggest that if business scholars and practitioners are going to move forward the work on the moral judgment-moral action gap, then it will be helpful to return to the historical embeddedness of this gap problem.

The study of ethics is concerned with the question of “what is right?” Greek philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle examined issues such as right versus wrong and good versus bad. For these philosophers, morality found its meaning in the fact that it served to achieve personal needs and desires for happiness, avoid harm, and preserve goods required for the well-being of individuals and society. These goods include truth, safety, health, and harmony, and are maintained by moral, virtuous behavior. We call this a teleological approach because of its focus on results rather than on rules governing behavior (Lane 2017; Parry 2014).

One of the first of these moral philosophers was Socrates (470–399 B.C.). Socrates believed that through rational processes or reasoning we can discern truth, including universal moral truth. Thus, Socrates taught that a person’s essential moral function is to act rationally. He taught that “to know the good is to do the good” (Stumpf and Fieser 2003, p. 42), meaning that if an individual knows what is right, he or she will do it. On the other hand, Socrates acknowledged that humans frequently commit acts that they know to be wrong. The Greeks called this phenomena—knowing what is right but failing to act on that knowledge—akrasia. Akrasia, from the ancient Greek perspective, is what leads to wrong or evil doing (Kraut 2018). Footnote 2

Another perspective that will be helpful later on in our examination of current literature is that of Aristotle. Regarding moral functioning, Aristotle focused on the development of and reliance on virtues: qualities, such as courage, that motivate a person’s actions (Kraut 2018). These virtues are developed through social influences and practice, and they become an essential part of who a person is. Thus, rather than learning to reason about actions and their results, as Socrates would emphasize as the core of moral functioning, Aristotle emphasizes virtues that a person possesses and that motivate ethical behavior (Kraut 2018).

Like Socrates, German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1785/1993) claimed that moral judgment is a result of reasoning. However, rather than taking a teleological approach to morality, he held to deontological views. For Kant, moral behavior is defined by an overarching obligation or duty to comply with strict universal principles, valid independent of any empirical observation. According to this deontological view, an action is right or wrong in and of itself, not as defined by end results or impact on well-being. Simply put, people are obligated out of duty to perform certain moral actions (Johnson 2008; Kant 1785/1993). In summary, for Socrates, Aristotle, and Kant, the emphasis is on knowledge and cognition.

This reliance on knowledge and cognition continued on from Socrates to Kant and on to the American moral psychologist Kohlberg (1927–1987). Kohlberg advocated a theory that sought to describe how individuals mature in their abilities to make moral decisions.

Before discussing Kohlberg further, we note that his work has had an enormous impact on academic research as whole. His research has been cited over 70,000 times. In the last 5 years alone, he has been cited between 2000 and 3500 times each year. Within business, his theory of cognitive moral development is widely discussed, commonly used as a basis for research, and frequently covered in the standard textbooks for business ethics courses. Thus, to say that the field has moved past him is to deny the reality of the literature and experience of business ethics as a whole. With that in mind, any careful examination of how to better bridge the moral judgment-moral action gap in behavioral ethics must address Kohlberg’s ideas.

Socrates’ belief that “to know the good is to do the good,” which reflects the importance in Greek thought of arriving at truths through reasoning, influenced Kohlberg’s emphasis on the chief role of rationality as the arbiter for discerning moral universals (Stumpf and Fieser 2003, p. 42). Kohlberg also embraced Aristotle’s notion that social experiences promote development by stimulating cognitive processes. Moreover, his emphasis on justice morality reflects Aristotle’s claims that virtues function to attain justice, which is needed for well-being, inner harmony, and the moral life.

Kohlberg’s thinking was heavily influenced by Jean Piaget, who believed that children develop moral ideas in a progression of cognitive development. Piaget held that children develop judgments—through experience—about relationships, social institutions, codes of conduct, and authority. Social moral standards are transmitted by adults, and the children participate “in the elaborations of norms instead of receiving them ready-made,” thus creating their own conceptions of the world (Piaget 1977, p. 315).

According to Piaget, children develop a moral perception of the world, including concepts of fairness and ideas about right and wrong. These ideas do not originate directly from teaching. Often, children persist in these beliefs even when adults disagree (Gallagher 1978). In his theory of morality, presented in The Moral Judgment of the Child, Piaget philosophically defined morality as universal and obligatory (Ash and Woodward 1987; Piaget 1977). He drew on Kantian theory, which emphasized generating universal moral maxims through logical, rational thought processes. Thus, he rejected equating cultural norms with moral norms. In other words, he rejected the moral relativity that pervaded most research in human development at the time (Frimer and Walker 2008).

In the tradition of Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development, Kohlberg launched contemporary moral psychology with his doctoral paper in 1958. His structural development model holds that the stages of moral development emerge from a person’s own thoughts concerning moral issues. Kohlberg believed that social experiences play a part in moral development by stimulating our mental processes. Thus, moral behavior is rooted in moral and ethical cognitive deliberation (Kohlberg 1969; Levine et al. 1985).

Kohlberg investigated how people justify their decisions in the face of moral dilemmas. Their responses to these dilemmas established how far within stages of moral development a person had progressed. He outlined six discrete stages of moral reasoning within three overarching levels of moral development (Kohlberg 1971a), outlined in Table 1 below. These stages were centered in cognitive reasoning (or rationality).

Table 1 Kohlberg’s six stages of moral developmentKohlberg claimed that the moral is manifest within the formulation of moral judgments that progress through stages of development and could be demonstrated empirically (Kohlberg 1971a, b). In this way, Kohlberg shifted the paradigm for moral philosophy and moral psychology. Up to this point, from the modern, Western perspective, most empirical studies of morality were descriptive (Lapsley and Hill 2009). Most research chronicled how various groups of peoples lived their moral lives and what the moral life consisted of, not what universal moral principles should constitute moral life. Kohlberg made the bold claim that individuals should aspire to certain moral universal principles of moral reasoning, and furthermore, that these principles could be laid bare through rigorous scientific investigation.

According to Kohlberg, an individual’s moral reasoning begins at stage one and develops progressively to stage two, then stage three, and so on, in order. Movement from one level to the next entails re-organization of a form of thought into a new form. Not everyone can progress through all six stages. According to Kohlberg, it is quite rare to find people who have progressed to stage five or six, emphasizing that his idea of moral development stages was not synonymous with maturation (Kohlberg 1971a). That is, the stages do not simply arise based on a genetic blueprint. Neither do they develop directly from socialization. In other words, new thinking strategies do not come from direct instruction, but from active thinking about moral issues. The role of social experiences is to prompt cognitive activity. Our views are challenged as we discuss or contend with others. This process motivates us to invent more comprehensive opinions, which reflect more advanced stages of moral development (c.f., Kohlberg 1969).

Reflecting Piaget and thus Kantian ethics, Kohlberg claimed that his stages of moral development are universal. His sixth stage of moral development (the post-conventional, universal principles level) occurs when reasoning includes abstract ethical thinking based on universal principles. Footnote 3

For Kohlberg, moral development consisted of transformations in a person’s thinking–not as an increased knowledge of cultural values that leads to ethical relativity, but as maturing knowledge of existing structures of moral judgment found universally in development sequences across cultures (Kohlberg and Hersh 1977). In other words, Kohlberg sought to eliminate moral relativism by advocating for the universal application of moral principles. According to him, the norms of society should be judged against these universal standards. Thus, Kohlberg sought to demonstrate empirically that specific forms of moral thought are better than others (Frimer and Walker 2008; Kohlberg 1971a, b).

Lapsley and Hill (2009) discuss the far-reaching ramifications of how Kohlberg moralized child psychology: “He committed the ‘cognitive developmental approach to socialization’ to an anti-relativism project where the unwelcome specter of ethical relativism was to yield to the empirical findings of moral stage theory” (p. 1). Footnote 4 For Kohlberg, a particular behavior qualified as moral only when motivated by a deliberate moral judgment (Kohlberg et al. 1983, p. 8). His ‘universal’ moral principles, then, were not so universal after all. Lapsley and Hill (2009) note that this principle of phenomenalism “was used as a cudgel against behaviourism (which rejected both cognitivism and ordinary moral language)” (p. 2).

This section of the article examines Kohlberg’s underlying assumptions and limitations. Although Kohlberg’s work is historically important and currently influential, this article proposes that business ethicists should avoid mis-application of and over-reliance on his framework.

To begin, Kohlberg assumes that the essence of morality is found in cognitive reasoning, mirroring Greek and Kantian thought. While such an assumption fit his purposes, we must move beyond this to understand ethical decision making more holistically (Sobral and Islam 2013). We know that the ability to reason does not always lead humans to act morally. Morality is more central to human existence, and reasoning is only one of multiple human activities that achieve the ends of morality (c.f., Ellertson et al. 2016). If we were to use Kohlberg’s assumption, we would assume that as long as someone is capable of advanced moral reasoning (as with Kohlberg’s use of hypothetical situations), we need not worry about that person’s actions. However, empirical studies by Hannah et al. (2018) indicate that although a person might demonstrate advanced moral reasoning in one role, the same person might show moral deviance in another role. Thus, recent research suggests that moral identity is multi-dimensional and ethical decision making is quite complex. Future work should consider the true, yet limited role of rationality in moral behavior and moral decision making (see Table 2).

Table 2 Summary of research directionsKohlberg also assumes that all humans proceed universally through moral development and that when fully developed—for those who do reach the highest level of reasoning—everyone will exhibit the same moral reasoning. If we are to build on this assumption, many questions are left unanswered about the easily observable differences both within and between individuals. For example, recent research by Sanders et al. (2018), suggests that in leaders who have high levels of moral identity, those who are authentically proud (versus leaders who are hubristically proud) are more likely to engage in ethical behavior. We call on researchers to study differences and limitations in moral processing that come from individual differences including past experiences, upbringing, age, personality, and culture. With such research, we will be able to better understand and reconcile differences regarding ethical issues and behavior.

Continuing to follow Kohlberg’s emphasis on universalism may limit our consideration of the real impact of social norms. We call on management scholars to investigate the importance of social, organizational, and individual norms rather than unwittingly assuming that universal principles should govern all organizational affairs. Certainly, some actions in business are universally unethical, but an assumption of absolute universal norms may limit organizational development, creative decision making, and the innovative power that comes from diversity of an individual’s social and cultural background. For example, empirical research by Reynolds et al. (2010) suggests that humans are moral agents and that their automatic decision-making practices interact with the situation to influence their moral behavior. Also, research by Kilduff et al. (2016) demonstrates how rivalry can increase unethical behavior. Future research on how situations and social norms affect behavior may help scholars to better predict, understand, and prevent moral judgment-action gaps and ethical conflicts between different individuals. Moral Domain Theory, which will be discussed later, provides one example of how to handle this question.

Kohlberg’s work does not directly address the moral judgment-action gap. For Kohlberg, until a person functions at the sixth stage of moral development, any immoral behavior roots from an inability to reason based on universal principles. However, his theory does not adequately explain the behavior of individuals who clearly understand what is moral–yet fail to act on that understanding (c.f., Hannah et al. 2018). This is yet another reason why as scholars we must question the claim that cognitive reasoning is central to the nature of morality. We call on business ethics scholars to design and test theoretically rigorous models of moral processing that connect gaps between judgment and action.

Moving forward, we do not disagree with Kohlberg’s notion that social interactions are important to moral reasoning, and we invite researchers and practitioners to consider what social experiences in the workplace could promote ethical development. Are some experiences, reflective practices, exercises, ethics training programs, or cultures more effective at promoting ethical behavior? For example, empirical research by Gaspar et al. (2015) suggests that how an individual reflects on past misdeeds can impact that person’s future immoral behavior. Future research could examine which experiences are most impactful, as well as when, why, and how these experiences affect change. Thus far we have reviewed the early work in moral development, including Socrates, Aristotle, Kant, Piaget, and Kohlberg. The remainder of the article discusses more recent theories.

The remainder of this paper will review how some researchers have built on Kohlberg’s assumptions and how others have successfully challenged them. In reviewing the theories of these researchers, remaining gaps in understanding will be discussed and future possible directions will be offered. Four areas of moral psychology research will be reviewed as follows: (1) Neo-Kohlbergian research, which builds upon Kohlberg’s original “rational moral judgments” approach, (2) Moral Identity research, which examines how moral identity is a component of how individuals define themselves and is a source for social identification, (3) Moral Domain research, which sees no moral judgment-action gap and assumes that social behavior stems from various domains of judgment, such as moral universals, cultural norms, and personal choice, and (4) Moral Automaticity research, which emphasize the fast and automatic intuitive approach in explanations of moral behavior.

Rest (1979, 1984, 1999) extended Kohlberg’s work methodologically and theoretically with his formulation of the Defining Issues Test (DIT), which began as a simple, multiple-choice substitute for Kohlberg’s time-consuming interview procedure. The DIT is a means of activating moral schemas (general knowledge structures that organize information) (Narvaez and Bock 2002). It is based on a component model that builds on Kohlberg’s stages of moral development—an approach he called ‘Neo-Kohlbergian.’ Rest (1983) maintained that a person must develop four key psychological qualities to become moral: moral sensitivity, moral judgment, moral motivation, and moral character. Without these, a person would have many gaps between his or her judgment and behavior. With 25 years of DIT research, Rest and others (Rest et al. 2000; Thoma et al. 2009) have found some support for the DIT and the model.

Although Rest built on Kohlberg’s work by emphasizing the role of cognitive moral judgments, he moved beyond the idea that the essence of morality is found in reasoning. Under the Neo-Kohlbergian approach, dealing with the moral became a more multifaceted endeavor, and many intricate theories of moral functioning—including moral motivation—have followed.

The work of Rest and his colleagues, along with Kohlberg’s foundation, has become a ‘gold standard’ in the minds of some management scholars (Hannah et al. 2011). Rest’s work has proven promising in its ability to explain the gap between moral cognition and behavior. However, his four-component model has also been criticized for assigning a single level of moral development to each respondent. Curzer (2014) points out that people develop at different rates and across different spheres of life, and that Rest’s Defining Issues Test (DIT) is not specific enough in its assessment of moral development. Future research could explore this criticism and analyze other methods for identifying, measuring, and improving moral development.

Blasi (1995) subscribed to a Neo-Kohlbergian point of view as he expanded on Kohlberg’s Cognitive Developmental Theory by focusing on motivation, an area of exploration not within the purview of Kohlberg’s main research. Though, toward the end of his career, Kohlberg did become more interested in the concept of motivation in his research (Kohlberg and Candee 1984), his empirical findings illuminate an individual’s understanding of moral principles without shedding much light on the motivation to act on those principles. According to Kohlberg, proficient moral reasoning informs moral action but does not necessarily explain it completely (Aquino and Reed 2002). Kohlberg’s own findings showed moral reasoning does not necessarily predict moral behavior.

Though his research builds on Kohlberg’s by emphasizing the role of cognitive development, Blasi’s focus on motivation represents a philosophical shift that provides a basis for moral identity research. Researchers in moral identity, though they agree with Kohlberg on some aspects of moral behavior, find the meaning of morality in characteristics or values that motivate a person to act. Because these components of identity are defined by society and deal with outcomes that a decision maker seeks, the philosophy of moral identity is more teleological than deontological. The philosophical definition of morality held by moral identity theorists influenced the way they studied moral behavior and the judgment-action gap.

Blasi introduced the concept of ‘the self’ as a sort of mediator between moral reasoning and action. Could it be that ‘the self’ was the source for moral motivation? Up until then, most of Kohlberg’s empirical findings involved responses to hypothetical moral dilemmas which might not seem relevant to the self or in which an individual might not be particularly engaged (Giammarco 2016; Walker 2004). Blasi’s model of the self was one of the first influential theories that endeavored to connect moral cognition (reasoning) to moral action, explaining the moral judgment-action gap. He proposed that moral judgments or moral reasoning could more reliably connect with moral behavior by taking into account other judgments about personal responsibility based upon moral identity (Blasi 1995).

Blasi is considered a pioneer for his theory of moral identity. His examination has laid a foundation upon which other moral identity scholars have built using social cognition research and theory. These other scholars have focused on concepts such as values, goals, actions, and roles that make up the content of identity. The content of identity can take a moral quality (e.g., values such as honesty and kindness, goals of helping, serving, or caring for others) and, to one degree or another, become central and important in a person’s life (Blasi 1983; Hardy and Carlo 2005, 2011). Research by Walker et al. (1995) shows that some individuals see themselves exhibiting the moral on a regular basis, while others do not consider moral standards and values particularly relevant to their daily activities.

Blasi’s original Self Model (1983) posited that three factors combine to bridge the moral judgment-action gap. The first is the moral self, or what is sometimes referred to as ‘moral centrality,’ which constitutes the extent to which moral values define a person’s self-identity. Second, personal responsibility is the component that determines that after making a moral judgment, a person is responsible to act upon the judgment. This is a connection that Kohlberg’s model lacked. Third, this kind of self-consistency leads to a reliable, constant uniformity between judgment and action (Walker 2004).

Blasi (1983, 1984, 1993, 1995, 2004, 2009) and Colby and Damon (1992, 1993) posit that people with a moral personality have personal goals that are synonymous with moral values. Blasi’s model claims if one acts consistently according to his or her core beliefs, moral values, goals, and actions, then he or she possesses a moral identity or personality. When morality is a critical element of a person’s identity, that person generally feels responsible to act in harmony with his or her moral beliefs (Hardy and Carlo 2005).

Since Blasi introduced his Self Model, he has elaborated in more detail on the structure of the self’s identity. He has classified two distinct elements of identity: first, the objective content of identity such as moral ideals, and second, the modes in which identity is experienced, or the subjective experience of identity. As moral identity matures, the basis for self-perception transitions from external content to internal content. A mature identity is based on moral ideals and aspirations rather than relationships and actions. Maturity also brings increased organization of the self and a refined sense of agency (Blasi 1993; Hardy and Carlo 2005).

Blasi believes that moral identity produces moral motivation. Thus, moral identity is the source for understanding or bridging the moral judgment-action gap. However, some researchers (Frimer and Walker 2008; Hardy and Carlo 2005; Lapsley and Hill 2009) have noted that Blasi’s ideas are quite abstract and somewhat inaccessible. Furthermore, empirical research supporting his notions is limited. Moreover, Blasi’s endorsement of the first-person perspective on the moral has made it difficult to devise empirical studies. Empirical research on Blasi’s model often involves self-report methods, calling into question the validity of self-perceived attributes. In addition, the survey instruments that rate character traits often exhibit arbitrariness and variability across lists of collections of virtues hearkening back to the ‘bag of virtues’ approach that Kohlberg sought to move beyond (Frimer and Walker 2008).

On the other hand, some researchers have investigated the concept of ‘moral exemplars,’ presumably under the assumption that they possess moral identities. Colby and Damon’s (1992, 1993) research on individuals known for their moral exemplarity found that these individuals experienced “a unity between self and morality” and that “their own interests were synonymous with their moral goals” (Colby and Damon 1992, p. 362). Hart and Fegley (1995) compared teenage moral exemplars to other teens and found that moral exemplars are more likely than other teens to describe themselves using moral concepts such as being honest and helpful. Additional research using self-descriptions found similar results (Reimer and Wade-Stein 2004). This implies that to maintain ethical character in the workplace managers may want to hire candidates who describe themselves using moral characteristics.

Other identity research includes Hart’s (2005) model, which strives to identify a moral identity in terms of five factors that give rise to moral behavior (personality, social influence, moral cognition, self and opportunity). Aquino and Reed (2002) propose that definitions of self can be rooted in moral identity. This concept of self is organized around moral characteristics. Their self-report questionnaire measures the extent to which moral traits are integrated into an individual’s self-concept. Cervone and Tripathi (2009) stress the need for moral identity researchers to step outside the field of moral psychology, shift the focus away from the moral and engage general personality theorists. This allows moral psychologists to access broader studies in personality and cognitive science and to break out of what they see as the compartmentalized discourse within moral psychology.

In summary, the main concern of moral identity theory is how unified or disunified a person is, or the level of integrity an individual possesses. For moral psychologists, an individual with integrity is unified and consistent across all contexts. Because of this unification and consistency, that person experiences fewer lapses (or gaps) in his or her moral judgments and moral actions (Frimer and Walker 2008).

Moral identity theory represents a philosophical belief that morality is at the core of personhood. Rather than focusing simply on the processes or functioning of moral development and ethical decision making, moral identity scholars look more deeply at what motivates moral behavior, and they make room for the concept of agency. Similarly, Ellertson et al. (2016) draw on Levinas to explain that morality is more central to human existence than simply the processes it includes.

The philosophy of virtue ethics arose from Aristotle’s views of the development of virtues (Grant et al. 2018). Virtue ethics theorizes that any individual can obtain real happiness by pursuing meaning, concern for the common good, and the trait of virtue itself, and that by doing so such an individual will develop virtuous qualities that further increase his or her capacity to obtain real happiness through worthwhile pursuits (Martin 2011).

Virtue ethics also posits that individuals with enough situational awareness and knowledge can correctly evaluate their own virtue, underlying motivations, and ethical options in a given situation (Martin 2011). Grant et al. (2018) explain that researchers of virtue ethics explore virtue as being context specific, relative to the individual, and developing over a lifetime. Therefore, virtue ethics considers moral decision making to be both personal and contextual, and defines ethical decisions as leading to actions that impact the common good and contribute to an individual’s real happiness and self-perceived virtue.

Although empirical research has found evidence of the constancy of individuals’ virtue characteristics under different situations, research suggests virtues are not necessarily predictive of actual ethical behavior (Jayawickreme et al. 2014). Empirical evidence of the application of the theory of virtue ethics at the individual level is lacking; a recent review of thirty highly cited virtue ethics papers found only two studies that collected primary empirical data at the individual level (Grant et al. 2018). Thus, we call on ethics scholars to investigate the development and situational or universal influence of virtue states, traits, and characteristics, as well as their impact on happiness and other outcomes.

We invite management scholars to utilize the findings summarized in this section as they research how to effectively identify, socialize, and leverage candidates possessing virtuous characteristics and moral integrity. Future research can explore the feasibility of hiring metrics centered on ethical integrity. We note the difficulty scholars have had in designing a tool for accurately assessing ethical integrity and in separating the concept from ethical sensitivity (Craig and Gustafson 1998). We also note the opportunity for more research to discover and improve instruments and measures to assess ethical integrity and subsequent development of high moral character.

As with most moral psychology research, ‘domain theory’ also stems from Kohlberg’s foundational research because it emphasizes the role of cognition in moral functioning. However, the work of theorists in this branch of psychology differs philosophically from the work of Kohlberg. Domain theory incorporates moral relativity to an extent that Kohlberg would likely be uncomfortable with. For them, the study of moral behavior is less about determining how humans ought to behave and more about observing how humans do behave. This ‘descriptive’ approach to morality is reflected in the majority of the theories through the end of this section.

Elliot Turiel and Larry Nucci are prominent domain theorists; they distinguish judgments of social right and wrong into different types or categories. For Nucci (1997), morality is distinct from other domains of knowledge, including our understanding of social norms. For domain theorists, social behavior can be motivated by moral universals, cultural norms, social norms, or even personal choice (Turiel 1983). Thus, social judgments are organized within domains of knowledge. Whether an individual behaves morally depends upon the judgments that person makes about which domain takes precedence in a particular context.

Nucci (1997) asserts that certain types of social behavior are governed by moral universals that are independent from social beliefs. This category includes violence, theft, slander, and other behaviors that threaten or harm others. Accordingly, research suggests that notions of morality are derived from underlying perceptions about justice and welfare (Turiel 1983). Theories of this sort define morality as beliefs and behavior related to treating others fairly and respecting their rights and welfare. In this sense, morality is distinct from social conventions such as standards of fashion and communication. These social norms define what is correct based on social systems and cultural traditions. This category of rules has no prescriptive force and is valuable primarily as a way to coordinate social interaction (Turiel 1983).

Turiel (1983, 1998) elaborates on the differences between the moral and social domain in his Social Domain Theory. In contrast to Blasi, he proposes that morality is not a domain in which judgments are central for some and peripheral for others, but that morality stands alongside other important social and personal judgments. To understand the connection between judgment and action, Turiel believes it is necessary to consider how an individual applies his or her judgments in each domain—moral, social, and personal (Turiel 2003).

Turiel’s social-interactionist model places behaviors that harm, cause injustice, or violate rights in the ‘moral domain.’ He claims that the definition of moral action is derived in part from criteria given in the philosophy of Aristotle where concepts of welfare, justice, and rights are not considered to be determined by consensus or existing social arrangements, but are universally valid. In contrast, actions that involve matters of social or personal convention have no intrinsic interpersonal consequences, thus they fall outside the moral domain. Individuals form concepts about social norms through involvement in social groups.

Turiel and Nucci’s work does not accept the premise that a moral judgment-action gap exists (Nucci 1997; Turiel 1983, 1998). They explain inconsistencies between judgment and behavior as the result of individuals accessing different domains of behavior. Thus, a judgment about which domain of judgments to prioritize precedes action. While an action may be inconsistent with a person’s moral judgment, it may not be inconsistent with that person’s overarching judgments that have higher priority. In other words, the person can know something is right, but in the end decide that he would rather do something else because in balancing his moral, personal, and social concerns, something else won out as seeming more important in the end. This particular aspect of Turiel’s model could be compared to Blasi’s personal responsibility component in which after a moral judgment is made, the person decides whether he has a responsibility in the particular moment or situation to act upon the judgment. Kohlberg’s research did not sufficiently address this element of responsibility to act.

Even though Turiel and Nucci recognize the prescriptive nature of behavior in the moral domain, they assert that the individual must make a judgment about whether it merits acting upon, or whether another sphere of action takes precedence. In other words, Turiel and Nucci may deem a particular moral action to be more important than action in the social or personal conventional sphere. However, unless the individual deems it so, there is no moral failure. The individual decides which sphere takes priority at any given time. The notions of integrity, personal responsibility, and identity as the origin of moral motivation (Blasi 1995; Hardy and Carlo 2005; Lapsley and Narvaez 2004) do not apply within Turiel’s social-interactionist model.

Dan Ariely, Francesca Gino, and others have discovered some interesting findings about activating the moral domain through triggers such as recall of the Ten Commandments or an honor code (Ariely 2012; Gino et al. 2013; Hoffman 2016; Mazar et al. 2008). However, research in this area is still in its infancy, and other scholars have not always been able to replicate the results (c.f., Verschuere et al. 2018). Future research could examine factors that determine why a certain sphere of action takes precedence over other spheres in motivating specific behaviors. For example, which factors impact an individual’s decision to act within the moral domain or within the social sphere? How can the moral domain be triggered? Why does or doesn’t one’s training or knowledge (such as the ability to recall culturally accepted moral principles such as the Ten Commandments) predict one’s ethical behavior?

In a similar vein to Turiel and Nucci, Bergman’s Model (2002) accepts an individual to be moral, even if that individual does not act upon his or her moral understanding. He finds the moral in the relationships among components of reasoning, motivation, action, and identity. With this model he seeks to answer the question raised by Turiel’s model, ‘If it is just a matter of prioritizing domains of behavior, why be moral?’ He asserts that his model preserves the centrality of moral reasoning in the moral domain, while also taking seriously personal convention and motivation, without succumbing to a purely subjectivist perspective (c.f., Bergman 2002, p. 36).

Bergman strives to articulate the motivational potential of moral understanding as truly moral even when it has not been acted upon. He does not assume that moral understanding must have an inevitable expression in action as did Kohlberg. Thus, Bergman provides another context for thinking about the problem of the judgment-action gap. He focuses on our inner moral intentions. He believes that when people behave morally, they do so simply because they define themselves as moral; acting otherwise would be inconsistent with their identity (Bergman 2002).

The assumptions underlying domain theory present several dangers to organizations. Moral Domain Theory assumes, with Kohlberg, that the essence of morality is in the human capability to reason, and that there is no moral issue at hand unless it is recognized cognitively. This creates the possibility of excusing individuals from the responsibility of the outcome of their actions. Even though Kohlberg believed in universal moral rules, the fact that he based such a belief in reasoning and empirical evidence allows those who build on his theory to create a morally acceptable place for behaviors that one deems reasonable even when such behaviors negatively impact the well-being of self or others. The question for management scholars is if we are willing to accept the consequences of such assumptions. We call on scholars to challenge these assumptions, such as by researching on a deeper level where morality really comes from and what it implies for decision making in organizations.

On the other hand, Moral Domain Theory addresses the influence of social norms, which is an important moral issue that Kohlberg’s research did not address. For example, empirical research by Desai and Kouchaki (2017) suggests that subordinates can use moral symbols to discourage unethical behavior by superiors. As we suggested earlier, future research should examine the influence of organizational, cultural, and social norms, symbols, and prompts. Even where universal norms do not prohibit an action, a person may be acting immorally according to expectations established within organizations or relationships. We call on scholars to consider if and when certain norms specific to a situation, organization, community, relationship, or other context may or may not (and should or should not) override universal principles. Research of this nature will help clarify what is ethically acceptable.

The philosophies of the researchers we will describe in this section begin to move away from Kohlberg’s assumption that morality is found in deliberate cognitive reasoning and the assumption that universal moral standards exist. For scholars in the moral automaticity realm, morality is based on automatic mental processes developed through evolution to benefit our individual and collective social survival. However, while they discuss moral judgments in terms of automatic rather than deliberate judgments, they still hold that the meaning of morality is found in the judgments that humans make.

Additionally, accounts of morality focused on automatic, neurological processes conflict with ideas of free will and personal responsibility. These accounts rely on the concept of determinism, or the belief that all actions and events are the predetermined, inevitable consequences of various environmental and biological processes (Ellertson et al. 2016). If these processes are really the basis of morality, some critics argue we are reduced to creatures without individuality. There is clearly a balance between automatic and deliberative processes in human moral behavior that allows for individual differences and preserves the idea of agency. We propose that while automatic processes certainly play a role in moral decision making, that role is to assist in a more fundamental purpose of our existence as humans (Ellertson et al. 2016). With this in mind, we summarize some of the most prominent research based on moral automaticity, summarize the research that argues for the existence of moral schemas and moral heuristics, then suggest directions for future research.

Narvaez and Lapsley (2005) have argued that John Bargh’s research provides persuasive empirical evidence that automatic, preconscious cognition governs a large part of our daily activities (e.g., Bargh 1989, 1990, 1996, 1997; Uleman and Bargh 1989). Narvaez and Lapsley (2005) assert that this literature seems to thoroughly undermine Kohlberg’s assumptions. Bargh and Ferguson (2000) note, for example, that “higher mental processes that have traditionally served as quintessential examples of choice and free will—such as goal pursuit, judgment, and interpersonal behavior—have been shown recently to occur in the absence of conscious choice or guidance” (p. 926). Bargh concludes that human behavior is not very often motivated by conscious, deliberate thought. He further states that “if moral conduct hinges on conscious, explicit deliberation, then much of human behavior simply does not qualify” (c.f., Narvaez and Lapsley 2005, p. 142).

Haidt’s (2001) views on the moral take the field in the intuitive direction. He focuses on emotional sentiments, some of which have been seen in the previous arguments of Eisenberg (1986) and Hoffman (1970, 1981, 1982) as well as the original thinking of Hume (1739/2001, 1777/1960), who concerned himself with human ‘sentiments’ as sources of moral action. Haidt claims that “the river of fMRI studies on neuroeconomics and decision making” gives empirical evidence that “the mind is driven by constant flashes of affect in response to everything we see and hear” (Haidt 2009, p. 281). Hoffman (1981, 1982) provides an example of these affective responses that Haidt refers to. He gives evidence that humans reliably experience feelings of empathy in response to others’ misfortunes, resulting in altruistic behavior. In Hoffman’s foundational work, we see that altruism and other pro-social behaviors fit in with empirical findings from modern psychological and biological research.

Haidt’s Social Intuitionist Model (SIM), has brought a resurgence of interest in the importance of emotion and intuition in determining the moral. He asserts that the moral is found in judgments about social processes, not in private acts of cognition. These judgments are manifest automatically as innate intuitions. He defines moral intuition as “the sudden appearance in consciousness, or at the fringe of consciousness, of an evaluative feeling (like-dislike, good-bad) about the character or actions of a person, without any conscious awareness of having gone through steps of search, weighing evidence, or inferring a conclusion” (Haidt 2001, p. 818).

Haidt asserts that “studies of everyday reasoning show that we usually use reasoning to search for evidence to support our initial judgment, which was made in milliseconds” (2009, p. 281). He believes that only rarely does reasoning override our automatic judgments. He does not like to contrast the terms emotion and cognition because he sees it all as cognition, just different kinds: (1) intuitions that are fast and affectively laden and (2) reasoning that is slow and less motivating.

Haidt focuses on innate intuitions that are linked to the social construction of the ethics of survival. He sees action as moral when it benefits survival (Haidt 2007). He argues that humans “come equipped with an intuitive ethics, an innate preparedness to feel flashes of approval or disapproval toward certain patterns of events involving other human beings” (Haidt and Joseph 2004, p. 56). Haidt proposes two main questions that he believes are answered by his Social Intuitionist Model: (1) Where do moral beliefs and motivations come from? and (2) How does moral judgment work?

His answer to the first question is that moral views and motivation come from automatic and immediate emotional evaluations of right and wrong that humans are naturally programmed to make. He cites Hume who believed that the basis for morality comes from an “immediate feeling and finer internal sense” (Hume 1777/1960, p. 2).

To answer the second question (‘How does moral judgment work?’), Haidt explains that brains “integrate information from the external and internal environments to answer one fundamental question: approach or avoid?” (Haidt and Bjorklund 2007, p. 6). Approach is labeled good; avoid is bad. The human mind is constantly evaluating and reacting along a good-bad dimension regarding survival.

The Social Intuitionist Model presents six psychological connections that describe the relationships among intuitions, conscious judgments, and reasoning. Haidt’s main proposition is that intuition trumps reasoning in moral processing (Haidt and Bjorklund 2007). Moral judgment-action gaps, then, appear between an action motivated by intuition and judgments that come afterwards. Applied to Kohlberg’s empirical study, this would imply that the reasoning he observed served not to motivate decisions but to justify them after the fact.

This approach suggests that ethical behavior is driven by naturally programmed emotional responses. Recent research by Wright et al. (2017) suggests that moral emotions can influence professional behavior. Other work conducted by Peck et al. (1960) shows that social influences, especially in family settings, stimulate character development over time. They also dismiss the importance of the debate between automatic and cognitive judgments by showing that people who have developed the highest level of moral character judge their actions “either consciously or unconsciously” and that “the issue is not the consciousness, but the quality of the judgment” (Peck et al. 1960, p. 8).

Monin et al. (2007) also strive to move beyond the debate that pits emotion or intuition against reason, vying for primacy as the source for the moral. They assert that the various models that seek to bridge the judgment–action gap are considering two very different proto-typical situations. First, those who examine how people deal with complex moral issues find that moral judgments are made by elaborate reasoning. Second, those who study reactions to alarming moral misconduct conclude that moral judgments are quick and intuitive. Benoit Monin and his colleagues propose that researchers should not arbitrarily choose between the one or the other but embrace both types of models and determine which model type has the greater applicability in any given setting (Monin et al. 2007).

Narvaez (2008a) contends that Haidt’s analysis limits moral judgment to the evaluation of another person’s behavior or character. In other words, his narrow definition of moral reasoning is limited to processing information about others. She wonders about moral decision making involving personal goals and future planning (Narvaez 2008a).

Narvaez (2008a) also believes that Haidt over-credits flashes of affect and intuition and undervalues reasoning. In her view, flash affect is just one of many processes we use to make decisions. Numerous other factors affect moral decisions along with gut feelings, including goals, mood, preferences, environmental influences, context, social pressure, and consistency with self-perception (Narvaez 2008a). We call on scholars to investigate whether, when, how, and with which level of complexity people wrestle with moral decisions. We also suggest researchers consider investigating whether there is anything that organizations can do to move people away from fast and automatic decisions (and toward slow and thoughtful decisions), and whether doing so motivates more ethical choices.

Haidt and Narvaez both believe that morality exists primarily in evolved brain structures that maximize social survival, both collectively and individually (Narvaez 2008a, b). Narvaez asserts that Haidt’s Social Intuitionist Model includes biological and social elements but lacks a psychological perspective. Narvaez (2008a) finds the moral ultimately in “psychobehavioral potentials that are genetically ingrained in brain development” as “evolutionary operants” (p. 2). To explicate these evolutionary operants, she refers to her own model of psychological schemas that humans access to make decisions. She notes that Haidt’s idea of modules in the human brain is accepted by many evolutionary psychologists but that such assertions lack solid empirical evidence in neuroscience (2008a).

In contrast, Narvaez’s schemas are brain structures that organize knowledge based on an individual’s experience (Narvaez et al. 2006). In general, Schema Theory describes abstract cognitive formations that organize intricate networks of knowledge as the basis for learning about the world (Frimer and Walker 2008).

Schemas facilitate the process of appraising one’s social landscape, forming moral identity or moral character. Narvaez terms this “moral chronicity” and claims that it explains the automaticity by which many moral decisions are made. Individuals “just know” what is required of them without engaging in an elaborate decision-making process. Neither the intuition nor the activation of the schemas is a conscious, deliberative process. Schema activation, though mostly shaped by experience (thus the social aspect), is ultimately rooted in what Narvaez (2008b) refers to as “evolved unconscious emotional systems” that predispose responses to particular events (p. 95).

Narvaez’s ‘Triune Ethics Theory’ (2008b) explains her idea of unconscious emotional systems. This research proposes that these emotional systems are fundamentally derived from three evolved formations in the human brain. Her theory is modeled after MacLean’s (1990) Triune Brain Theory, which posited that these formations bear the resemblance of animal evolution. Each of the three areas has a “biological propensity to produce an ethical motive” (Narvaez 2008b, p. 2). With these formations, animals and humans have been able to adapt their behavior according to the challenges of life (Narvaez 2008b). Emotional systems, because of their central location, can interact with other cognitive formations. Thus, a thought accompanies every emotion, and most thoughts also stimulate emotion. Narvaez’s model is a complex system in which moral behavior (though influenced by social events) is determined almost completely from the structures of the brain.

Some researchers (Bargh and Chartrand 1999; Gigerenzer 2008; Lapsley and Narvaez 2008; Sunstein 2005) assert that intuition and its consequent behavior are constructed almost completely through environmental stimuli. Bargh and Chartrand (1999) assert that “most of a person’s everyday life is determined not by their conscious intentions and deliberate choices but by mental processes that are put into motion by features of the environment and that operate outside of conscious awareness and guidance” (p. 462). Our brains automatically perceive our environment, including the behavior of other people. These perceptions stimulate thoughts that lead to actions and eventually to patterns of behavior. This sequence is automatic; conscious choice plays no role in it (see, e.g., Bargh and Chartrand 1999, p. 466).

Lapsley and Hill (2008) address Frimer and Walker’s original question of whether moral judgment is more deliberate or more automatic. They include Bargh and Chartrand (1999) in their list of intuitive models of moral behavior which they label ‘System 1’ models because they describe processing which is “associative, implicit, intuitive, experiential, automatic and tacit” as opposed to ‘System 2’ models where the mental processing is “rule based, explicit, analytical, ‘rational’, conscious and controlled” (p. 4). They categorize Haidt’s and Narvaez’s models as System 1 models because they are intuitive, experiential, and automatic.

Gigerenzer (2008) believes that intuitions come from moral heuristics. Moral heuristics are rules developed by experience that help us make simple moral decisions and are transferable across settings. They are shortcuts that are easier and quicker to process than deliberative, conscious reasoning. Thus, they are automatic in their presentation. They are fast and frugal. They are fast in that they enable quick decision making and frugal because they require a minimal search for information to make decisions.

Heuristics are deeply context sensitive. The science of heuristics investigates which intuitive rules are readily available to people (Gigerenzer and Selten 2001). Gerd Gigerenzer is interested in the success or failure of these rules in different contexts. He rejects the notion of moral functioning as either rational or intuitive. Reasoning can be the source of heuristics, but the distinction that matters most is between unconscious and conscious reasoning. Unconscious reasoning causes intuition, and—as with Haidt’s theories mentioned earlier—conscious reasoning justifies moral judgments after they are made (Lapsley and Hill 2008). In general, Gigerenzer asserts that moral heuristics are accurate in negotiating everyday moral behavior.

Sunstein’s (2005) model also claims that intuitions are generated by ‘moral heuristics.’ However, in contrast to Gigerenzer, he notes that heuristics can lead to moral errors or gaps between good judgment and appropriate behavior when these rules of thumb are undisciplined or decontextualized. This happens when we use heuristics as if they were universal truths or when we apply heuristics to situations that would be handled more appropriately with slower rational deliberation. Sunstein (2005) supports the view that evolution and social interaction cause the development of moral heuristics. Also, recent research by Lee et al. (2017) suggests an evolutionary account for male immorality, providing some support for the existence of an evolutionary origin and for the use of moral automaticity. To investigate the disagreement between Sunstein and Gigerenzer, we call on researchers to further examine the frequency, depth, and accuracy with which humans use moral heuristics.

Lapsley and Hill (2008) categorize the theories of Sunstein (2005) and Gigerenzer (2008) as System 1 models because the behavior they describe appears to be implicit, automatic, and intuitive. These models emphasize the automaticity of moral judgments that come from social situations. A person with a moral personality detects the moral implications of a situation and automatically makes a moral judgment (Lapsley and Hill 2009). For this kind of person, morality is deeply engrained into social habits.

Though Lapsley and Hill categorize heuristics models the same as Haidt’s, we observe that ‘intuition’ in the sense of heuristics means something very different to them than what it means to Haidt. In Haidt’s Social Intuitionist Model, learning structures developed through evolution are the source of automatic judgments. On the other hand, Sunstein’s (2005) intuitions come from ‘moral heuristics,’ which are quick moral rules of thumb that pop into our heads and can even be developed through reasoning. As researchers examine the roles of reasoning and intuition in moral decision making, they may consider breaking intuition into categories, such as intuitions that represent heuristics and intuitions that come from biological predispositions.

The models of moral functioning just described fall into the ‘intuitive’ category, though they are competing descriptions of how to meaningfully connect judgment and action. Frimer and Walker (2008) observe that on one hand, models based on deliberative reasoning may be the most explanatory in that they require individuals to engage in and be aware of their own moral processing; “The intuitive account, in contrast, requires a modicum of moral cognition but grants it permission to fly below the radar” (p. 339). In a way, it separates moral functioning from consciousness or the ‘self.’

The specialties of moral automaticity, moral schemas, and moral heuristics are interesting and promising areas for those interested in future research in ethical decision making. One reason is because these specialties are highly multidisciplinary. Philosophers, psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, neuroscientists, and others, in addition to business scholars, are throwing themselves into this area. A second reason is because some of the most interesting future research questions in this multidisciplinary field are interdisciplinary. Many of the unanswered questions are complex and must be addressed from many different angles and with a variety of tools.

Consider just two research questions: (1) How does individual meaning-making actually take place if biological evolution is the primary driver and architect of both our personal moral choices and subsequent ethical interpretations? (2) What type of real accountability is possible if brains are programmed to make moral and/or immoral choices? These types of questions lie at the heart of what it means to be a human being, and these are just a few of the theoretical questions in moral automaticity research.

Future research directions in the empirical examination of moral automaticity are just as fascinating. For example, (1) Where, when, and why does the brain light up when ethical decisions are made and reflected upon? (2) Which areas of the brain fire first when confronted with a difficult ethical situation? (3) What is the sequence that the brain fires in when experiencing moral disengagement? (4) How plastic is the brain as it relates to rewiring and strengthening neural pathways that will lead to more prosocial behavior? (5) What are the predominant dispositional and situational factors that lead the brain to heal from moral injury? (6) How do various situations, social settings, and personality differences interact to activate automatic and deliberative processes?

In summary, we call for future research in moral automaticity, moral schemas, and moral heuristics to shed light on the roots of moral action. Given the research supporting the role of automaticity in moral processing, we caution against relying too heavily on models that emphasize the preeminence of rational thinking until research further examines this phenomenon. We also call for research examining the same subjects both in situations that require deliberative processing and in situations that are inherently intuitive. We suggest the use of fMRI studies to observe the activity of different sections of the brain—those associated with rational, cognitive processes and those associated with intuitive judgments—during unique situations.

Even in the earliest stages of moral philosophy, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle noted that people do not always act on the rational understanding they possess (Kraut 2018). They used the term “akrasia” to describe the phenomenon in which a person knows what is right but fails to act on that knowledge. This is commonly called the moral judgment-action gap.

Lawrence Kohlberg’s work (Kohlberg 1969, 1971a, b) is not only widespread in research, but also in business education today. His influential theory of cognitive moral development rests on the assumption that the ability to morally reason at a certain level is the primary core and driver of a person’s morality. Kohlberg’s work proposes that stages of moral development, which are defined at a universal level, are what is most fundamental. Although his ideas are important, recent research demonstrates his theorizing is insufficient in understanding and predicting the moral judgment-action gap (Hannah et al. 2018; Sanders et al. 2018). This article has provided various examples of other research that has successfully moved beyond Kohlberg’s assumptions (Aquino and Reed 2002; Grant et al. 2018). For this reason, we encourage ethics scholars to reconsider an overreliance on rationality in their research in behavioral business ethics. In Fig. 2, we show the major theories and the relationships between them.

Many scholars have presented research that specifically addresses the judgment-action gap. For example, moral identity theory and virtue ethics explore how a person’s self-perception motivates moral behavior (Blasi 1983; Hardy and Carlo 2005, 2011; Walker et al. 1995). However, more empirical evidence and better theories and models are needed that show how a person develops moral identity and moral character. Future studies can examine the ways in which moral identity leads to ethical decision making.

Moral domain theory suggests that the judgment-action gap does not exist and that the gap can be understood through additional domains of reasoning (ex. self-interest, social interest, etc.) used to evaluate the moral implications of a given situation (Bergman 2002; Nucci 1997; Turiel 2003). What we do not fully understand is what causes a person to recognize moral implications in the first place and how individuals apply different domains in decision making. Given the conflicting research findings (e.g., Mazar et al. 2008; Verschuere et al. 2018), we call for more research that shows what stimuli can trigger a person to view a decision as a moral decision as opposed to a decision in which social influences or personal preferences take precedence.

Some scholars oppose the idea that conscious reasoning governs most moral behavior. For example, Bargh (1989, 1990, 1996, 1997, 2005; Bargh and Ferguson 2000; Uleman and Bargh 1989) and Haidt (2001, 2007, 2009) have provided evidence that people make ethical decisions based on automatic intuitions. As Narvaez (2008b) has pointed out, however, we would be wrong to assume that all decisions are based solely on flashes of intuition. What we do not know is how factors such as situation, personality, and cultural background influence the relative and complimentary roles of conscious reasoning and intuition in moral behavior. We call for research that investigates the influence of these factors on moral processing.

Even Haidt (2009) recognizes the existence of moral reasoning, though he claims that it occurs only to rationalize an intuitive decision after it has been made. Scholars who discuss the development and use of heuristics (Gigerenzer 2008; Sunstein 2005) show how past reasoning about moral situations—perhaps the kind of reasoning that Haidt refers to—can influence the development of behavioral rules of thumb. These rules, or “heuristics,” appear to function automatically after they have been developed through cognition over the course of a person’s experiences. What we do not understand is the extent to which heuristics are consistent with an individual’s conscious moral understanding. We call for research that explores the formation of heuristics and their reliability in making real-life ethical decisions that are consistent with a person’s moral understanding.

This article shows that different theories point us in different directions within the fields of moral psychology and ethical decision making. Thus, it is very difficult to form a holistic understanding of moral development and processing. With this in mind, our most urgent call is for scholars to develop a holistic framework of moral character development and a comprehensive theory of ethical decision making. These types of models and theories would serve as powerful tools to fuel future empirical research to help us understand why people do not always act on their moral understanding. More robust research is critical to understanding how to prevent devastating ethical failures and how to foster ethical courage.