The First World War took place from the 28 July 1914 to the 11 November 1918. An estimated twenty million people died.

It was a global war fought between the Allies (the French Empire, the British Empire, the Russian Empire, the United States of America and others) and the Central Powers (the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire).

As the war drew to a close in 1918, German supplies and troops were exhausted from four years of warfare. In contrast, by 1918, the British had improved their tactics and equipment and the United States of America had arrived to support the Allied powers on the battlefields.

It was combination of these factors that led to the Allied Powers achieving victory.

Losing the war caused far reaching upheaval in Germany. This section will cover how the aftermath of the First World War led to the creation of Germany’s new democratic government, the Weimar Republic

Kaiser Wilhelm II was the Emperor of Germany and the Commander-in-Chief of the German armed forces.

In November 1918 the war drew to a close as allied troops advanced. In response, the Imperial Navy, previously loyal to the Kaiser, mutinied

Meanwhile, there was also significant unrest at home. It had become clear to the German people that losing was inevitable. They were disillusioned with the politics and harsh conditions of war, and many lent their support to the extremist parties which had emerged all over Germany.

On 9 November 1918, having lost the support of the military, and with a revolution underway at home, Kaiser Wilhelm II was forced to abdicate his throne and flee Germany for Holland.

Power was handed to a government led by the leader of the left-wing Social Democratic Party, Friedrich Ebert.

The armistice was agreed on 11 November 1918, but the formal peace treaty was not agreed until the following year. This peace treaty became known as The Treaty of Versailles. It was signed on 28 June 1919.

The discussions about the treaty between Britain, France and the USA began in January 1919. Germany was not invited to contribute to these discussions.

Germany assumed that the 14-point plan , set out by President Woodrow Wilson of the USA in January 1918, would form the basis of the peace treaty. However, France, who had suffered considerably in the war, was determined to make sure that Germany would not be able to challenge them again.

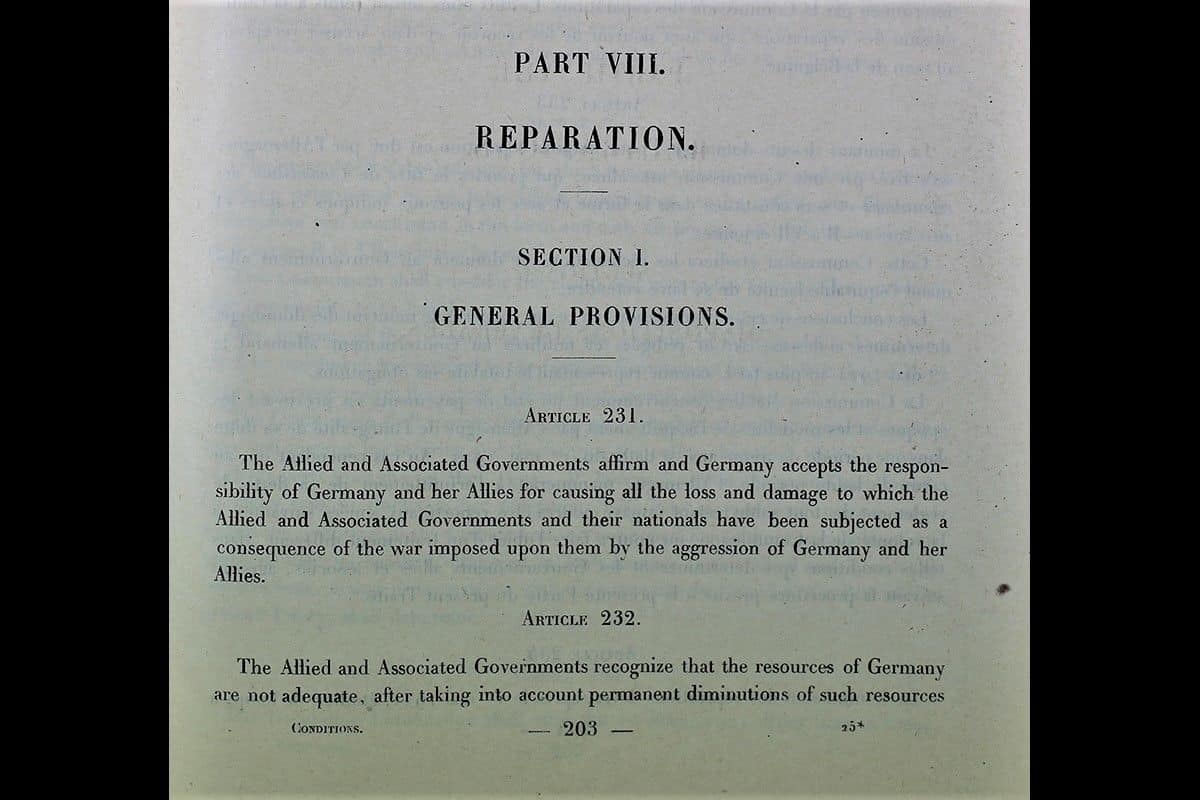

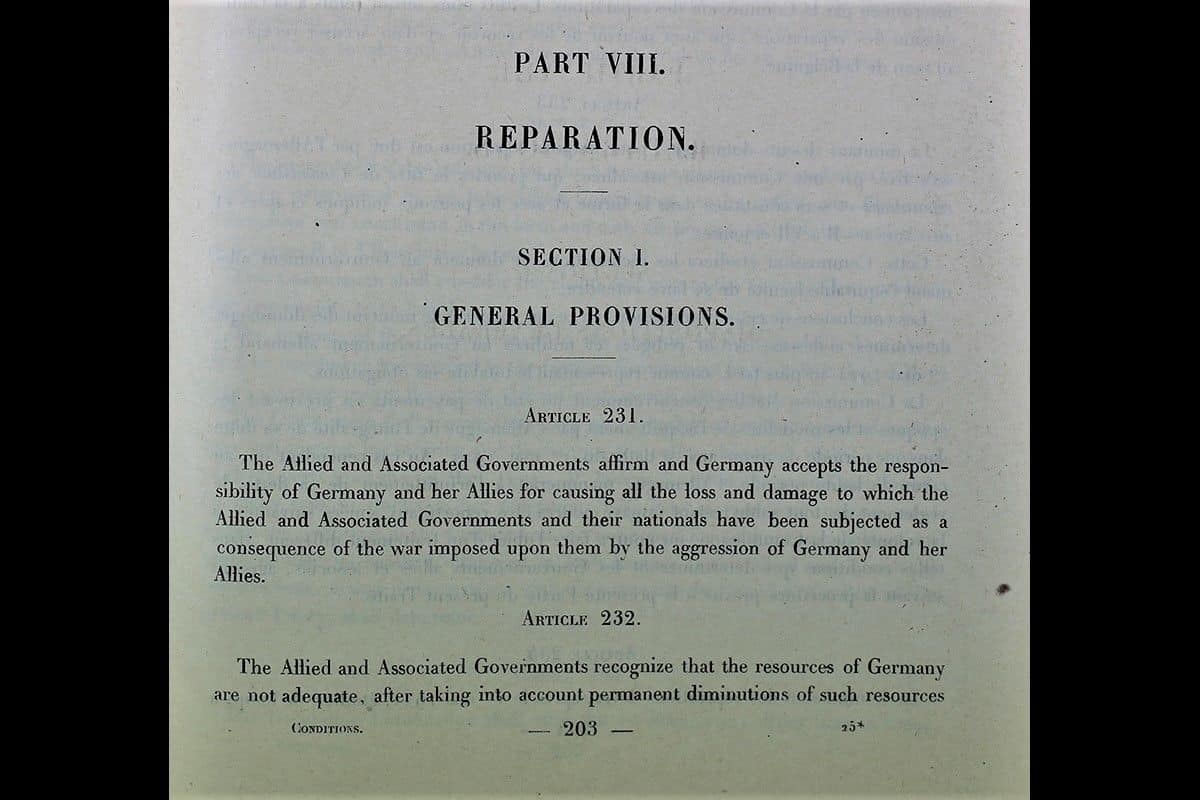

Under clause 231, the ‘War Guilt Clause’, Germany had to accept complete responsibility for the war. Germany lost 13% of its land and 12% of its population to the Allies. This land made up 48% of Germany’s iron production and a large proportion of its coal productions limiting its economic power.

The German Army was limited to 100,000 soldiers, and the navy was limited to 15,000 sailors. As financial compensation for the war, the Allies also demanded large amounts of money known as ‘reparations’.

The Treaty of Versailles was very unpopular in Germany and was viewed as extremely harsh. Faced with the revolutionary atmosphere at home, and shortages from the conditions of war, the German government reluctantly agreed to accept the terms with two exceptions. They did not accept admitting total responsibility for starting the war, and they did not accept that the former Kaiser should be put on trial.

The Allies rejected this proposal, and demanded that Germany accept all terms unconditionally or face returning to war.

The German government had no choice. Representatives of the new parties in power, the SPD and the Centre Party, Hermann Müller and Johannes Bell, signed the treaty on the 28 June 1919.

Many Germans were outraged by the Treaty of Versailles. They regarded it as a ‘diktat’ – dictated peace. Müller and Bell were branded the ‘November Criminals’ by the right-wing and nationalist parties that opposed treaty.

Despite the war drawing to an end in 1918, conditions in Germany did not dramatically improve.

Initially, Allied forces still blocked shipments of food and supplies from entering Germany. Although some food and supplies got through, these were sparse and therefore expensive. The Stab-in-the-Back myth fed extreme nationalism, antisemitism and anti-communism. The new government was unpopular amongst large sections of the population, and some people still felt a loyalty to the Kaiser.

It was in the midst of these challenging circumstances that in late 1918 and early 1919 violent revolutions spread throughout Germany.

In January 1919, the Spartacist Uprising by the German Communist Party threatened Berlin. In April 1919, in the southern region of Bavaria, a communist state was established in Munich.

Faced with these threats to the newly established democratic government, President Ebert used the German army and the Freikorps to crush the revolutions.

These uprisings were defeated quickly, but with the Russian Revolution of 1917 fresh in the minds of the ruling and middle classes, there remained an extreme fear of revolutions disturbing the peace of Germany.